Judaism had sectarian faultlines in the Second Temple Era. The main ones were:

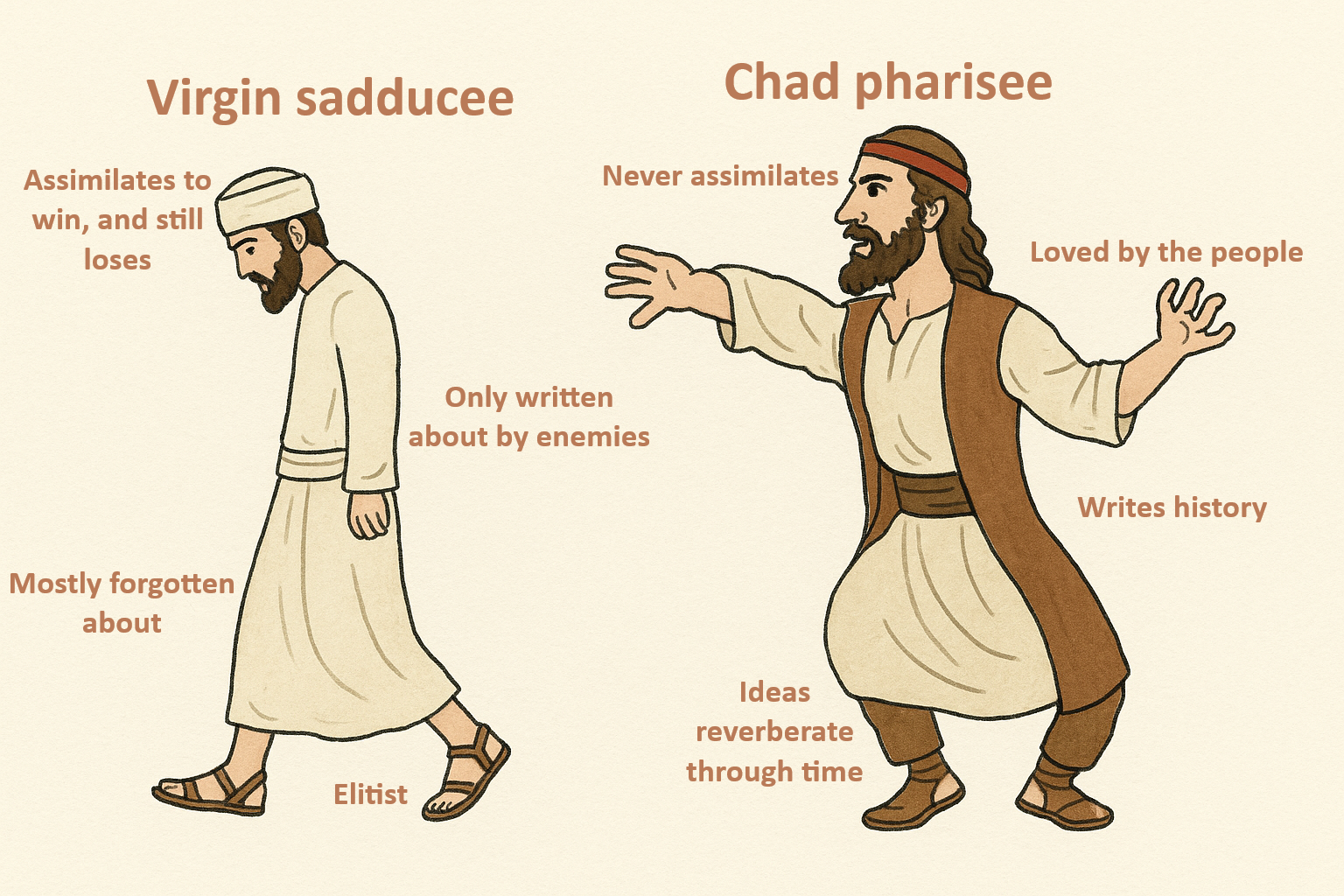

The pharisees are the group that evolved into the mainstream rabbinic Judaism of today after the destruction of the second temple in 70 AD. While priests controlled Temple rituals, rabbis studied and interpreted the Torah, beginning in the exile period after the destruction of the first Temple. They believed that all Jews ought to adhere to purity laws that applied to Temple services even outside the Temple. If we’re to trust Josephus, who was perhaps a pharisee himself, they were anti-elitist, and thus popular with the common folk.

In contrast, the Sadducees represented society’s elite, including priests and Judean state administrators, who were significantly Hellenized. They had a more literal interpretation of Biblical edicts, didn’t follow the oral Torah, and had different ideas about when different purity rules should be followed. They didn’t believe in any kind of afterlife, choosing to live luxuriously in this life instead. None of their own texts survive, and all the mentions we have of them are by people who hated them.

The Essenes were a monastic group responsible for the Dead Sea Scrolls. They led communal lives, with collective ownership and refusal to participate in trade. They didn’t sacrifice animals or use weapons unless in self-defense, and chose not to have slaves. In slightly less sane rules, some would avoid defecation on the Sabbath in order to maintain purity.

Zealots were aligned with the Pharisees, but were radically anti-Roman. They tried to force other Jews to join their struggle against the Romans by, for example, destroying decades’ worth of food and firewood to increase Jews’ desperation while under siege.

Jewish Christians were a growing faction of Jews who believed Jesus was the Messiah. Jewish Christians still continued to worship at synagogues with non-Christian Jews for centuries after the destruction of the Second Temple. Christianity and rabbinic Judaism were in this time much less orthodox and doctrinally homogeneous than today, and both were influenced by Hellenistic religion and philosophy.

After the destruction of the Second Temple, prospects for a third were grim. Jews needed to figure out how to do their religion without its centerpiece. The pharisees were prepared with the best answers for this, and so they prevailed—in contrast with many pagan faiths that faded after their civilizations encountered a loss. To prevent further sectarianism, rabbis were committed to debate as a value, encouraging these debates to happen within a single community, rather than developing schisms. Zealots were all wiped out, and Sadducees lost influence. Essenes were always marginal. Jewish Christians became just Christians, though when the overlap ended is hard to pin down.