I’ve read in several places that Arabs were identified as descendants of Ishmael even before the rise of Islam. I also came across claims that they practiced circumcision and avoided pork independently of any Abrahamic religion.

Curious about the origins of this identification and the customs surrounding it, I dug deeper. My two main questions were:

- Where and with whom does the identification of Arabs as Ishmaelites originate?

- Did the customs (like circumcision) come first, or the genealogical identification? How widespread were these behaviors?

So I looked into it. Here’s what I found.

One guy (probably) made it all up

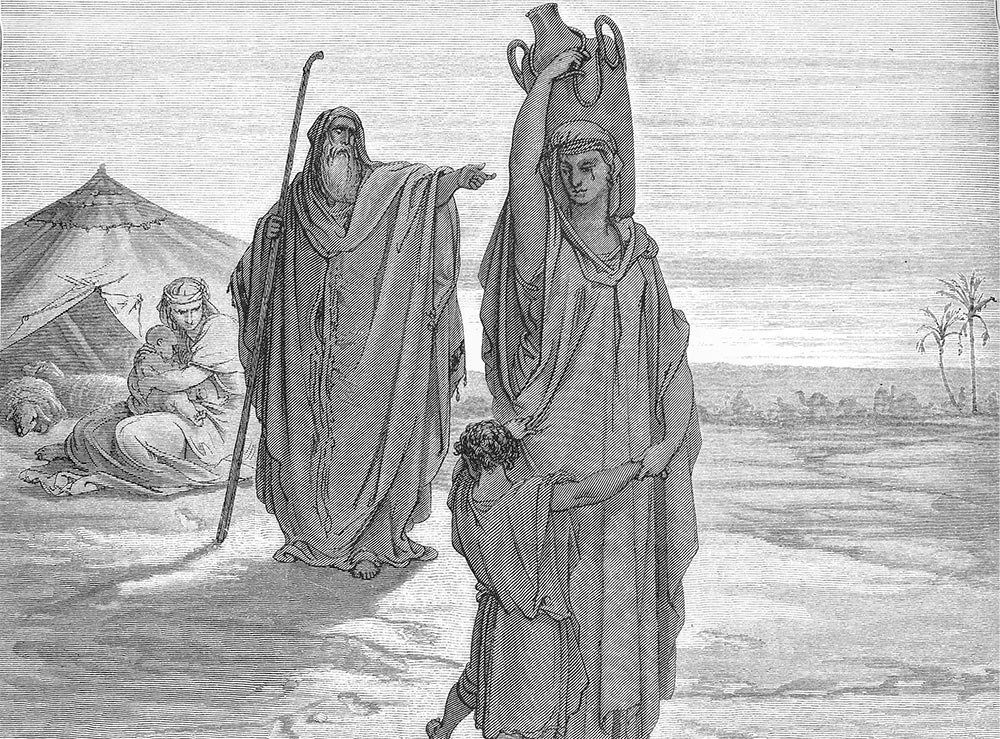

According to Fergus Millar’s book chapter Hagar, Ishmael, Josephus, And the Origins of Islam, the earliest clear and unambiguous identification of Arabs as Ishmaelites comes from Josephus, a first-century Jewish historian. In Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus links the Arab practice of circumcision at age thirteen to their descent from Ishmael:

Eight days later they promptly circumcised [Isaac]; and from that time forward the Jewish practice has been to circumcise so many days after birth. The Arabs defer the ceremony to the thirteenth year, because Ishmael, the founder of their race, born of Abraham’s concubine, was circumcised at that age.

Josephus mentions Arabs in other contexts too. In his retelling of the Joseph story, he refers to “Arab traders of the race of the Ishmaelites”, and elsewhere lists their genealogy based on Genesis 25:13–15. But while Genesis says the Ishmaelites “from Havilah to Shur which is opposite Egypt,” Josephus expands their domain significantly:

occupied the whole country extending from the Euphrates to the Red Sea and called it Nabatene, and it is these who conferred their names on the Arabic nation and its tribes in honour both of their own prowess and the fame of Abraham

Josephus was working within a Greek historiographical tradition that traced peoples to mythical or legendary founders—often with tangible implications for the self-identification and customs of those peoples.

But despite this Greek tendency to associate peoples with mythical ancestors, they don’t appear to have applied it to Arabs—until Apollonius Molon, a pagan Greek writer of the first century BC, proposed that Arabs descended from Abraham and Hagar.

I tried to track down Molon’s original text, but as far as I can tell, his written works are lost to time. The closest surviving version comes from Eusebius’Preaparatio Evangelica from the early 4th century AD, which quotes Molon via a retelling by Alexander Polyhistor:

…Molon, the author of the collection Against the Jews, says that at the time of the Deluge the man who survived departed from Armenia with his sons, being driven out of his home by the people of the land; and after crossing the intermediate country came into the mountain-district of Syria which was uninhabited.

After three generations Abraham was born, whose name is by interpretation “Father’s friend,” and that he became a wise man, and travelled through the desert. And having taken two wives, the one of his own country and kindred, and the other an Egyptian handmaiden, he begat by the Egyptian twelve sons, who went off into Arabia and divided the land among them, and were the first who reigned over the people of the country: from which circumstance there are even in our own day twelve kings of the Arabians, bearing the same names as the first.

This account is both later and filtered, not to mention ambiguous.

Could Josephus have used Molon’s Against the Jews as a source and expanded on it? And where did Molon get the idea in the first place? Unfortunately, we don’t know. Josephus was certainly familiar with Molon’s work, and it seems unlikely that a pagan writer would apply a biblical genealogy to the Arabs without some influence from Jewish tradition. (That said, I’m curious about the context for Molon—now mostly remembered for his anti-Semitism—adopting a Jewish narrative at all.)

Another possibility is that both Molon and Josephus were drawing from a broader cultural or oral tradition. But while it’s hard to rule that out—especially given how much post-biblical Jewish literature has been lost—there’s little evidence to support the idea. As Millar puts it: “explicit expressions of any conception of a significant relationship between Jews and Arabs are extremely rare outside Josephus.”

And given Josephus’s known habit of embellishing Biblical stories—often by inserting specific details where the text was vague—Millar sees the most plausible explanation as this: the genealogical link between Arabs and Ishmael was Josephus’s own invention.

What does the Bible say?

The only direct biblical reference linking Arabs to Ishmael appears in the Book of Jubilees, a second century BC retelling of Genesis. In chapter 20:16-17, it states:

And Ishmael and his sons, and the sons of Keturah and their sons, went together and dwelt from Paran to the entering in of Babylon in all the land which is towards the East facing the desert. And these mingled with each other, and their name was called Arabs, and Ishmaelites.

At first glance, this looks promising—could it have been a source for Josephus?

Unfortunately, it’s not that straightforward. This passage comes from Latin and Ethiopic Christian translations of Jubilees dating from at least the 6th century AD. These were translated from a Greek version, which itself was based on a now-lost Hebrew original. While we do have surviving Hebrew fragments of Jubilees, this particular passage isn’t among them.

Scholars agree that the Ethiopic translation is generally faithful to the lost Hebrew, but given the popularity by the 6th century of the idea that Arabs descended from Ishmael—especially among Christians—it’s entirely possible this passage reflects later influence. In particular, by this time the Christian view that Arabs had strayed from an originally Jewish or Abrahamic tradition had solidified.

The earliest Christian reference to the Ishmaelites’ historical and religious identity comes from Origen in the mid-third century. In Contra Celsum, he observes that Jews differentiated their practice of circumcision from that of the “Ishmaelite Arabs,” even though Ishmael was also a son of Abraham and had been circumcised. Around the same time, Eusebius, in his Praeparatio Evangelica, makes a similar point—writing that Ishmaelites in Arabia circumcised their sons at age thirteen. According to Millar, “[Eusebius’] dependence on Josephus (direct or indirect) is clear.”

Even setting aside the textual transmission issues, Jubilees itself isn’t part of the Hebrew Bible. It is, however, canonized in the Ethiopic Bible and was widely read by early Christian authors. But for Josephus, who didn’t belong to one of the Jewish sects that treated Jubilees as canonical, it likely didn’t carry scriptural authority.

As for the canonical Hebrew Bible, it contains references to both Ishmaelites and Arabs, but never links them explicitly. According to I. Ephʿal in his article “Ishmael” and the “Arab(s)”: A transformation of ethnological terms, the biblical references to Ishmaelites portray them as desert nomads, but so do references to many other groups. There’s nothing in the text that clearly identifies them as Arabs.

The Ishmaelites in the Hebrew Bible are most often associated with groups like the Midianites, Amalekites, Hagarites, and the “People of the East.” But mentions of these groups taper off after the mid-10th century BC—and no contemporaneous records from other cultures reference the Ishmaelites at all, including sources dealing with the peoples of the Arabian Peninsula.

The term “Arab” in the Bible is broader and more cultural than genealogical. It refers to nomadic desert-dwellers rather than a distinct ethnic group. The term appears relatively late, surfacing only from the second half of the 8th century BC onward, both in biblical and non-biblical sources. Its use as an ethnic label seems to be a much later development still.

What about the shared customs?

Even before Islam, Arabs were known to practice male circumcision and avoid eating pork. But how widespread were these practices, really?

This wasn’t the main focus of my reading, but I stumbled across a few relevant sources that are worth sharing. Maybe I’ll return to this topic in more depth another time—for now, here’s what I found.

In Herodotus’ Histories (5th century BC), he writes:

…the Colchians and Egyptians and Ethiopians are the only nations that have from the first practised circumcision. The Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine acknowledge that they learned the custom from the Egyptians, and the Syrians of the valleys of the Thermodon and the Parthenius, as well as their neighbors the Macrones, say that they learned it lately from the Colchians. These are the only nations that circumcise, and it is seen that they do just as the Egyptians. But as to the Egyptians and Ethiopians themselves, I cannot say which nation learned it from the other; for it is evidently a very ancient custom

Josephus, writing in the Antiquities of the Jews (late 1st century AD), responds to this directly:

[Herodotus] says withal that the Ethiopians learned to circumcise their privy parts from the Egyptians, with this addition, that the Phoenicians and Syrians that live in Palestine confess that they learned it of the Egyptians. Yet it is evident that no other of the Syrians that live in Palestine, besides us alone, are circumcised. But as to such matters, let every one speak what is agreeable to his own opinion.

This seems to suggest that Josephus identifies Jews as being a subset of the “Syrians of Palestine”, but rebuts Herodotus’ claim that all the inhabitants of the region were circumcised. Even so, as late as the 4th century AD, Epiphanius described circumcision as a widespread cultural practice—not limited to Jews or governed strictly by religious law:

What have the Ebionites to boast of in practising circumcision, when idolaters and the priests of the Egyptians observe it? But so also do the ‘Sarakēnoi,’ who are also called ‘Ismaēlitai,’ observe it, as do the Samaritans and Jews and Idumaeans and ‘Homēritai.’ But of these most do not practise this as a matter of the Law, but by a sort of unreflecting custom.

(Note that by this point, the names “Saracens” and “Ishmaelites” are already treated as interchangeable.)

On the subject of pork avoidance, the clearest reference I found is from Sozomenus’ Ecclesiastical History (440s AD), which also contains a rather idiosyncratic (i.e. false) view of the origin of the word “Saracen”:

As their mother Hagar was a slave, they afterwards, to conceal the opprobrium of their origin, assumed the name of Saracens, as if they were descended from Sarah, the wife of Abraham. Such being their origin, they practice circumcision like the Jews, refrain from the use of pork, and observe many other Jewish rites and customs.

Meanwhile, Theodoret of Cyrrhus, writing around the same time in his Philotheos Historia, describes “Ishmaelites” who converted to Christianity and gave up worshipping Aphrodite. Upon conversion, they also stopped eating the meat of asses and camels. Notably, pork isn’t mentioned—which might suggest they weren’t eating it to begin with.

Which leaves me with even more questions: Why weren’t they eating pork already? And why did they start following Jewish dietary customs when that wasn’t a requirement for Christians?

I have no idea.

Summing up

It seems likely that Josephus is the one responsible for introducing—or at least popularizing—this particular piece of misinformation. Whether he borrowed it from earlier sources or came up with it himself, we can’t say for certain. But what’s clear is that his version of the story caught on, especially among later Christian writers, and eventually filtered into Arab cultural memory.

I’ve been reading A History of the Muslim World: From Its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity by Michael Cook, and early in the book he tries to explain the unexplainable by laying out the preconditions for the rise of Islam. One of the conditions he proposes is that Islam’s success may have hinged on its ability to present itself not as a break with the past, but as a return to ancestral tradition—a revival, not a revolution.

But from today’s vantage point, that seems almost certainly false.

We can’t run the counterfactual in which Josephus never put this idea to paper, but it’s hard not to wonder what might have been. The rise of Islam is such a black swan event that even explaining it in hindsight feels like mere rationalization, as Cook himself acknowledges.

And yet, here we are, living in the post-truth era—created in part by a single first-century historian’s false claim. I think there’s something oddly beautiful about that.